A Creative Life

What is a "Creative Life" and how do you live it? I can't define this for others, I can only speak from my own experience in trying to lead a creative life of excellence during my lifetime.

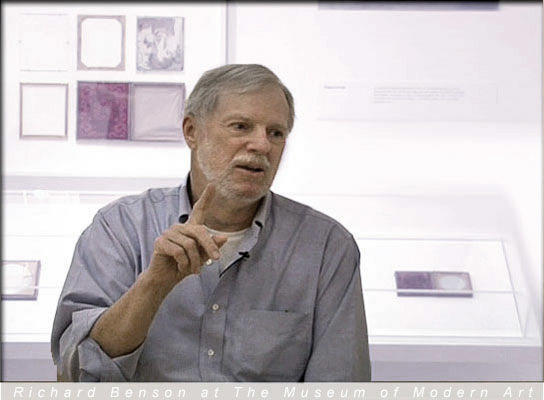

I know people that have picked up creative pursuits and artistic disciplines, worked these through to completion and then moved on to others, time and again. I am far simpler, for, when I "picked up" art in my early twenties I stuck with it and am still in it. Initially, my introduction to making art was as a painter, studying under the enigmatic and frustrating Tauno Kauppi and later at RISD with Mike Ashcraft. Soon, photography took on more prominence studying under Harry Callahan and a little later, Aaron Siskind. It didn't take long for photography to win me over completely. Photography became my life.

Did I know, almost 50 years ago, that photography could sustain me, provide an income working as a university teacher, or that I could maintain a consistently high creative output all those years? No idea. But a creative life involves just that: the requirement that new ideas, new approaches, and new projects spring forth time and time again, over a whole career.

A creative life needs to be more than just a person's vocation and/or avocation. How challenges are faced, how difficult times are handled, how problems are solved or managed all are part of the larger concept of a creative life. I once watched Frederick Sommer cooking hamburgers on the stove at his home in Prescott, AZ and understood that he was making art then just as much as he was when photographing with an 8 x 10 view camera in the desert. Or my brother-in-law, industrial designer Marc Harrison, long gone now almost twenty years, walking through an old home my wife and I had just bought, seeing its potential if walls were knocked down to let light in to our new home in Cambridge in 1982. Or Ezra Stoller, setting up lights at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire one autumn day in the 1970's, to color balance the interior lighting with the daylight outside on assignment to make a cover image of a new library for an architectural magazine.

I wish I was more flamboyant and more creative in other disciplines. Although I play the keyboard and think of this as a part of my creative pursuits, I am not so very good. I admire those that seem to be able to do anything and I admit to the narrowness of my efforts. I am all photography, all the time. While grateful that I chose a medium so difficult, elusive and challenging (and fulfilling, I might add) I recognize the sheer obsession with just one, while hopefully making good work, has meant I have excluded a great deal else from my life.

"Put art into everything you do", is something I have said to myself and my students over the years. This involves ritual, largely, or the kind of totality of existence a dancer displays when running to catch a bus. How we move when photographing, or approaching a subject through our extreme fluidity with the act, leaning on our intuition and muscle memory to feel what's right, when to change settings, focus or a lens. Practice, practice, practice, as the saying goes. Good art benefits from discipline, a strong work ethic, and a questioning spirit.

"I wonder what it would look like if I...?" has been another constant companion for many years. This is armchair philosophizing, of course. Thinking conceptually, trying to put this with that, a location in a certain light, a tool with a certain method, an approach with a way of printing, handling the file, or using this developer, this toner, this paper in the analog and darkroom days.

My creative life has been long and productive, for I have proven to be prolific, an endless challenge for curators and gallerists who would be happier with less to choose from. On the other hand, I don't know that I would feel as good about the work had I made less. At least for this artist, immersion into what I do seems to have been crucial. That's not to say that parenting, friendships, relationships, a family haven't loomed large, for they have and still do.

Ultimately, as a professional artist, I can't separate what I do from my work, nor should I. The way I choose to live my life affects my art; everything is input, whether we know it or not.

I believe that a creative life does not allow much for complacency, apathy, a lack of energy or drive, being uninquisitive, lazy, or unmotivated. "Garbage in, garbage out" applies here and is what separates those who really do versus those that are posers and trying to look like they do. This is an oversimplification but it is frustrating and demoralizing to see those that are new, brash and lacking in knowledge and experience speeding ahead, receiving acclaim and recognition for work that is clueless and uninformed of the history of the medium or current practice. A "Creative Life" implies longevity, a long track record of accomplishment and a significant contribution.

I've used this before but perhaps it can stand seeing the light of day again. This was the last paragraph I wrote in 2003 when applying to be a full professor at my university:

Thirty-five years ago, when the concept of being an artist for the rest of my life first dawned on me, I had little to show; no skills, little education, no ability to define what it would be like to be an artist and few mentors. But my job seemed clear: I needed to learn my chosen discipline and produce work. This I proceeded to do, learning as I went, adding a series of photographs or a group of pictures that were an idea, concept or an interest on top of a stack of others that would grow over a whole career. This program entailed life-long learning. Parts of my process would change: my understanding of the medium would grow and evolve during these years. Photography too would change; movements in contemporary art and society would affect me in obvious and subtle ways. However, the requirement was to make the best work I could, to stay active, to produce work that was qualitatively as consummate as I knew then how to make it. This I’ve done. As I grew and understood more about photography as an art form, and worked to master my technique and refine my aesthetic, I became more comfortable with my place in the discipline. I no longer was aspiring to be something. I was heavily engaged in the making. Finally, I have sought, quite simply, to make a contribution to the medium of photography.

A creative life? Well, yes, I believe I have.

Hershey PA

Hershey PA Thompson Springs Utah

Thompson Springs Utah Yountville, CA

Yountville, CA Monsters

Monsters Reggio Emilia, Italy

Reggio Emilia, Italy