Seeing

"Seeing" was the title for a book colleague and art historian Norma Steinberg and I conceived of and worked on in the 90s. It was written into a prospectus and submitted to a publisher. The book was never published.

The publisher we selected had been pursuing me for years, wanting me to write a photo textbook. Once we submitted the proposal they modified the book so extensively it was really no longer our book anymore. I believe they wanted our names and academic credentials as validation but not the book as we proposed. We walked away.

What was it? Seeing used my photographs and rationale for the way I worked as a foundation for a logic of looking at things photographically. It delved into photographs potential as way to arrive at a photographic vision and a photographic philosophy of seeing.

Norma was a colleague and friend and a remarkable addition to our Department at Northeastern. She taught our photo history course and always came to my classes' final critiques. She brought a unique perspective that included historical context.

The book was also specifically about looking at black and white photographs, although chapter 5 was to be titled "Color" to deal with my practice of always toning my black and white photographs.

I'm going to quote from the prospectus, written by Steinberg. This one, the proposal for chapter 7 called:

The Personal

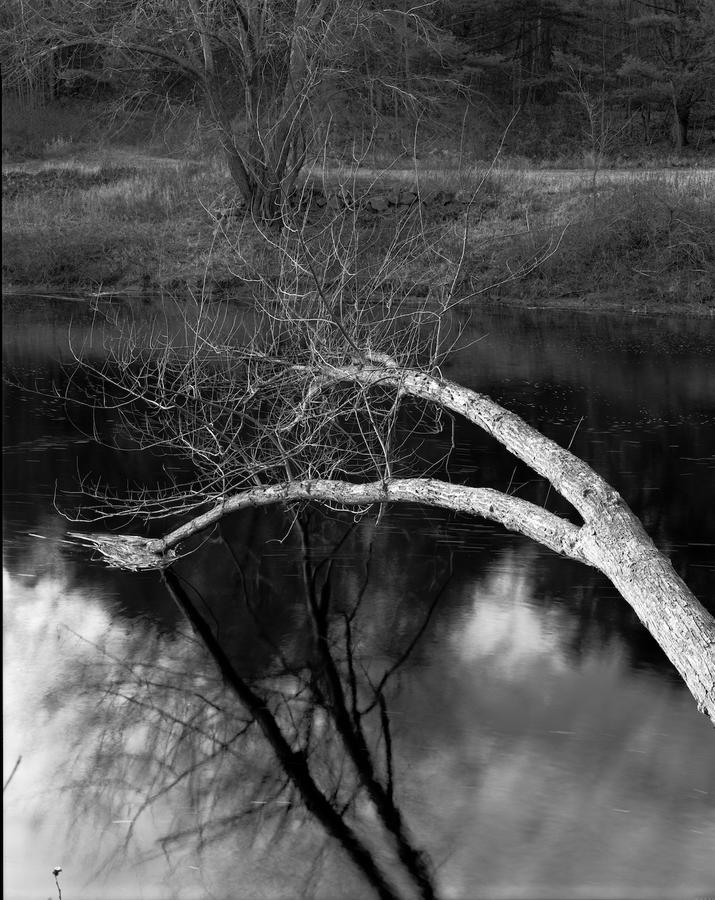

Throughout the history of photography, we read the same questions and responses about the nature of the medium-that it is either a mechanical medium of which we expect a truthful representation of reality, or that it is an art form, which is less truthful. As an artist Rantoul squeezes his pictures from within his own experiences, preferences, and feelings. It is a subjective process, involving decisions about where to go, when to stop to photograph, how to position the camera, what light to use, how to expose the film, how to process the film for the control of contrast, what size, tonality and color to make the print and so on. That is what is meant by photographers when they say "make photographs" rather than "take photographs" and it belies the idea that photography is an objective medium.

Or here, where she's explaining Fast and Slow (my term):

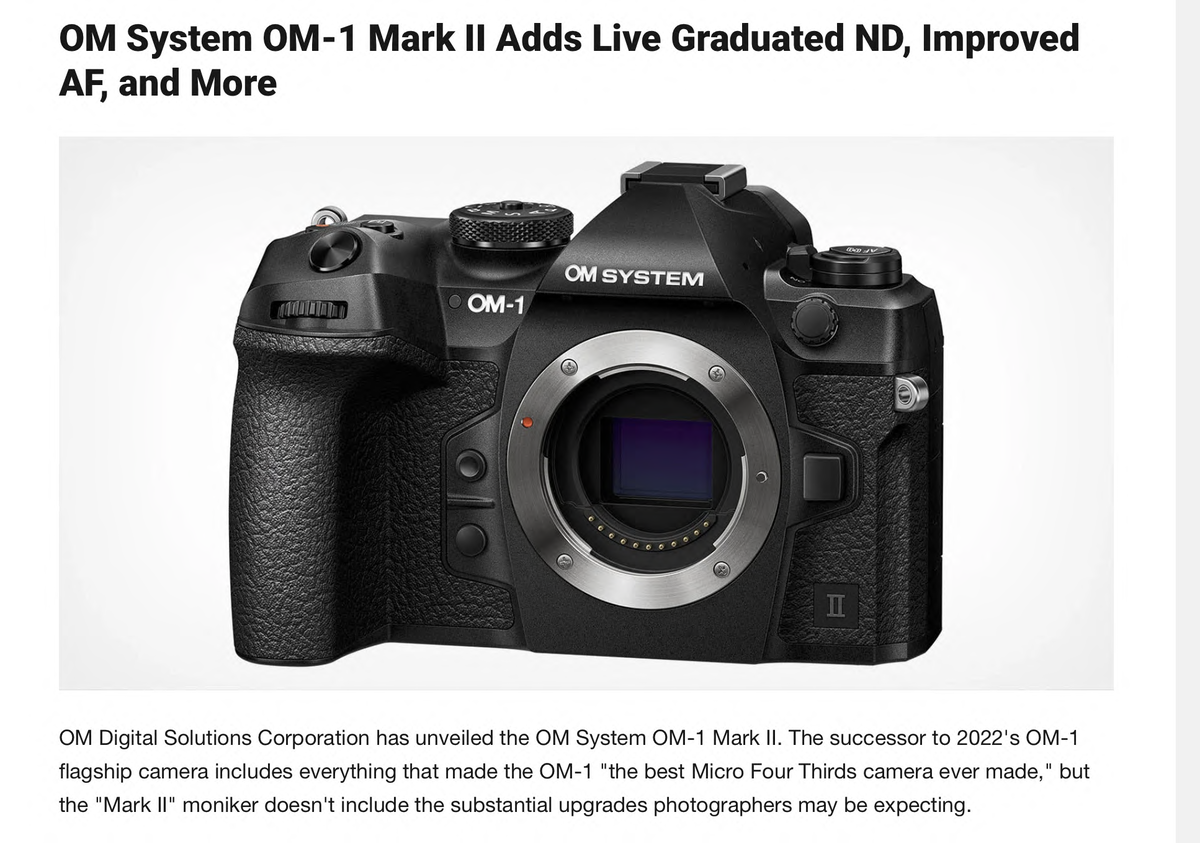

There are two meanings to the phrase "fast and slow." The first, more poetic, meaning is concerned with a directorial approach. A "slow" picture is one with obstructions or challenges to the viewer's ability to move through the space of the picture. A "fast" picture, on the other hand, permits the viewer's eye to move into visual depth. Sometimes the vertical lines move toward the center and at other times verticals bend outward. Slow photographs are planar and frontal, and often contain a visual screen across the picture plane. They may even be abstract, as for example, the New York or Gloucester pictures of Aaron Siskin. They may seem planar, as for example when a Rantoul landscape eliminates the sky and removes the sense of a horizon. In this definition of "fast and slow," the photographer's sense of design becomes important. Rantoul states: "A fast picture has visual depth with strong foreground-to-background information. My 'fast' pictures have prominent foregrounds and acute convergence." Sometimes this is the direct result of the equipment used because certain cameras have a propensity to tilt the scene at the edge. The camera as a definer of form will be discussed in several places throughout the book.

I'd correct this last by clarifying that it is probably the width of the lens that makes some photographs "faster".

The second meaning of the phrase is more literal-the actual time it takes to make the pictures, the choreography of the artist's movements through space, and the significance of that timing to the final work. This structural meaning of "fast and slow", relates to those bodies of work that take months or even years to complete as compared to the spontaneous series pictures described in Chapter One.

It is important to keep in mind that we were still firmly in the analog world of conventional film-based photography in the mid 90s and using prints made in my darkroom as our foundation.

Of course, we should have moved on to other publishers as we had a viable concept. I think we were so crushed at how this one publisher mislead us we gave up.

Last, it was a wonderful experience working with Norma on this project. She forced me to be focused, to express my concepts clearly and what I'd been teaching for years into a cohesive and cogent sequence of ideas.

As always your comments are welcome.