Photography's Hard

Photography's easy, right? Your phone makes great pictures. You don't really need a real camera anymore.

But photography's really hard if you want to use it knowledgeably, substantively, if you want to make art, if you want to extend it beyond the everyday concerns we all have to record our lives and share them with others. It is particularly difficult now that photographs are universal, infused into our lives in every aspect, filling every nook and cranny of our existence with their presence. Photography is now ubiquitous.

When I studied photography in the early 70's, photography as a means of creative expression was fairly new and certainly not universally understood. That meant that innovation was relatively easy. There was much to explore. Double expose, turn pictures upside down, superimpose, juxtapose, blur and scratch an emulsion, etc. Making statements that hadn't been made before wasn't so hard.

But if you want to make art with your camera now. If you want to avoid the insignificant, trite, banal, done-to-death and cliche, it is harder. If you want to innovate, make things never seen before, to rock the world with imagery that is breathtaking, aggressive, beautiful, and extraordinary.

Well, you're screwed, my friends, for photography as an art has somehow become something else, well over the era of being a new and exciting form of expression. Take landscape: impeccable and exquisite pictures of faraway lands glorified with the perfect time of day, the perfect light and the perfect resolution? Irrelevant and done to death. Why would a beautiful image shot in the mountains of, say, New Zealand have any possible relevance in today's world except in a "National Geographic" kind of way? When a "Google Images" search produces literally hundreds of the same kinds of pictures as yours, or worse, better than yours.

Let me remind you that these examples, obtained through a Google Images search, are usually anonymous, free for the taking. The only possible reason I can see for this kind of photography is to "put one in your quiver", to take the photograph yourself, to make a photograph that is right up there with the competition, to call it your own, to bask in the accomplishment that you went there, captured that with your camera, had the print made or made the print yourself, framed it or had it framed and hung it over your mantle in your living room for your family and friends to see with predictable oohs and aahs.

But art? I don't think so. Something else entirely.

I know this might provoke some controversy around the definition of "art" for art is used in all kinds of contexts, most of them making art more pedestrian. I also know I have opened the door to push back for there are many who believe

(Source: Google Images)

(Source: Google Images)

there is a place in art for this kind of photography. And no doubt, there are some very beautiful images being made in this way. But art? More like elegant description, enhanced documentation or interpretation.

So photography is hard because this is is simply not enough, to record our surroundings with fidelity. Yes, there's a place for this but real art, art that says something, that propels us forward, that does not confine itself to convention, that becomes significant historically, that is far more difficult and daunting and entails a higher level of responsibility.

The big mistake, of course, is this: assuming, because you like it and are proud of it, your friends and family like it and have urged you to enter the contest, to meet with the gallery director, the book editor, the museum curator, that these professionals will be impressed and moved to purchase your work, show it, publish it. But, from their point of view, please, tell me, what are they to do with your pictures?

In earlier times, perhaps as a holdover from the era of Edward Curtis and William Jackson that showed us the frontier of the American West in the late 1800s for the first time, you could get away with impressing this way. But not now, not when these below are right there for the taking:

Endless blue-sky landscapes, glorifications of existing places, postcard-perfect, idealized and beautifully rendered. Is that what you aspire to? Or do you want to go deeper, share your unique take on the world, use what is in front of your camera to comment, display and render with heart and intellect, to use photography's amazing abilities to convey with relevance, timeliness, and perspective?

What do you think? What do you want to say? What do you believe?

What's key here is this: it is all too easy to make pictures that are generic, cookie-cutter photographs that simply meet the norm, the contemporary conventional. Our job as artists is to go farther, to push our medium into forms of expression that extend ours and our audiences' understanding of this medium we choose and to signify our unique place in the world.

Cabela's, Nebraska, 2005

Cabela's, Nebraska, 2005

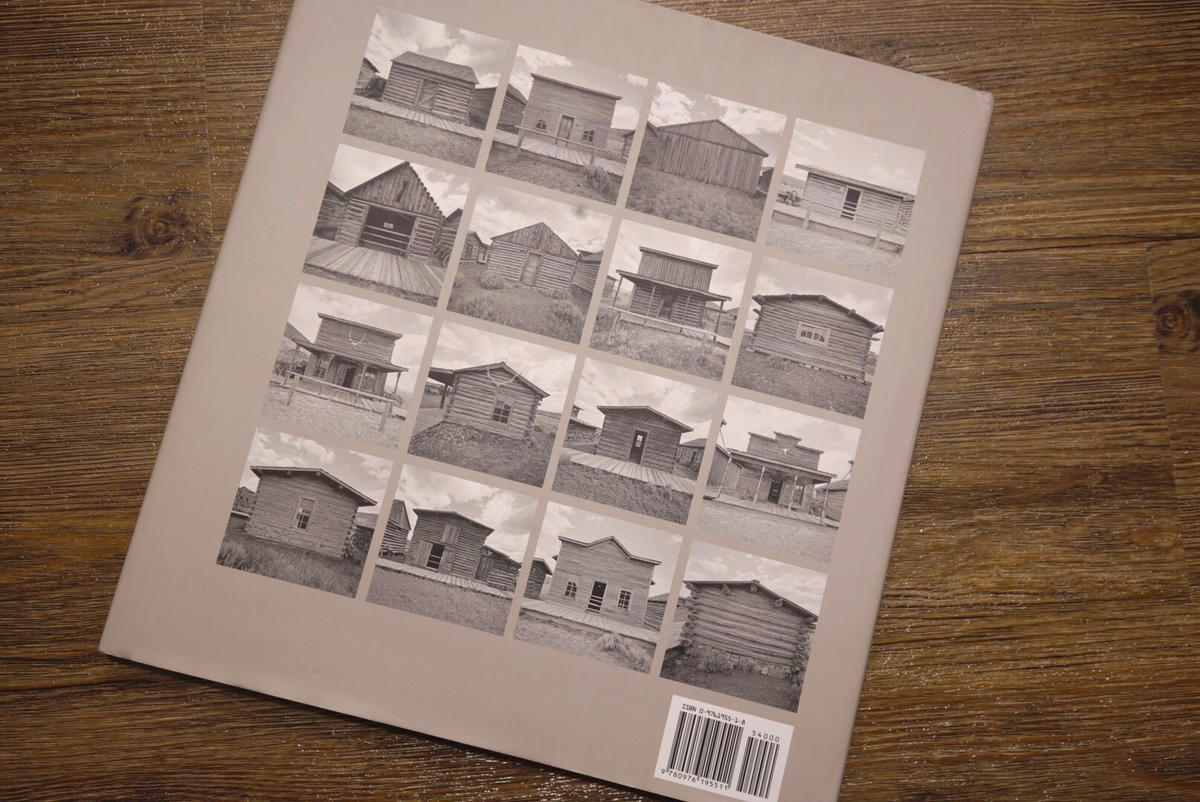

back cover American Series, Cody Wyoming, photographs by Neal Rantoul 2005

back cover American Series, Cody Wyoming, photographs by Neal Rantoul 2005

cut Xmas trees, Spruce Pine, NC

cut Xmas trees, Spruce Pine, NC

Museum of Health and Medicine, Bethesda, MD

Museum of Health and Medicine, Bethesda, MD

Paradise, CA 11/2019

Paradise, CA 11/2019

More reading: This article references my work circa 2011 and hits on some of the same themes: