The Hasselblad Superwide

Another in a series taking a look at some of the tools I have used to make my pictures over the years. Last month I did a couple of posts on the Rollei SL66. Next up we're going to look at the Hasselblad Superwide (SWC). The SWC is a camera that has a rich tradition across many types of photography. Developed in the 1950's to fit a very special lens made by Karl Zeiss to a camera body, it was a camera made to accommodate a lens rather than the other way around. It was also completely unique in the Hasselblad line of cameras and, indeed, across all of photography.

The camera used a fixed 38mm f3.5 Carl Zeiss Biogon lens, in a 120mm square format that used interchangeable backs. As it had no mirror, it was viewfinder-based with focusing determined by guessing the distance then setting the feet on the barrel of the lens. It had no meter, no electronics at all. It was also very small due to having no mirror so it really was a one-handed camera.

I had two of them. The first one I bought used in 1978 (from Phil Levine) and then sold it in 1984 to buy an 8 x 10 view camera. By 1996 I was back into one and bought it new. By this time its price had become very high and the body had been revised slightly.

What pictures did I make with it?

What pictures didn't I make with it!

It was the primary camera I used to make series work, my main vehicle of expression over my whole career. Here are a few, searchable on the gallery page of my site:

Nantucket

Yountville

Boston (in infrared)

Solothurn

Portland ( with a blog post explaining the pictures here)

Newtown

Summerhill

Old Trail Town

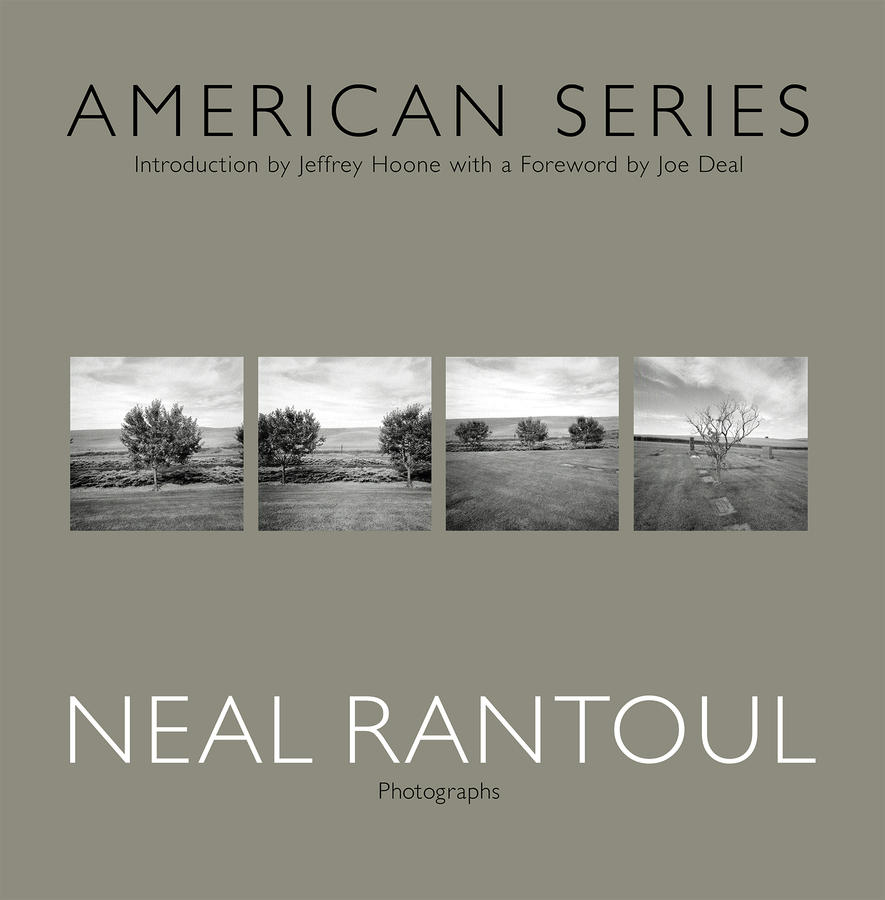

Hershey and on and on. All the photographs from the monograph published in 2006 : American Series

and on and on. All the photographs from the monograph published in 2006 : American Series

were made with the camera except for the wheat pictures, which were made with the 8 x 10.

Why was the camera so special? Quite simply it was the lens. 38mm on the 2 1/4 format is roughly equivalent to 25mm in 35mm. So this was a very wide lens. But it also was unique in that it fell off very little in sharpness and exposure in the corners and if kept level (hence the bubble level built into the finder) straight lines would stay straight. Plus, the lens was very sharp. The print of the boys on the dock from the Nantucket series is sitting downstairs at my home and is 43 inches square. It is very sharp.

Advanced students would occasionally approach me about this camera, thinking, if they liked my pictures, they might like to own a Superwide. Besides the obstacle of the camera's cost (about $5000!) the SWC was a highly specialized tool for making photographs. I would explain that this camera wasn't any kind of all-purpose tool to make pictures with. You had to be able to move in close to your subject and any work with an extremely wide-angle lens is always exacting. This usually discouraged them. I got so that I could guess the distance pretty well as there was no way to precisely check the focus except using the company's ground glass adapter. This was more for studio photographers and perhaps for some architectural work but it was cumbersome in the field. I would say 90% of the work I did with the camera was handheld. But over the years I got to know what I could and could not do with it. When it was the right tool for the job it was simply amazing.

I don't know if people have the same degree of connectedness with their cameras these days or not. And I generally don't like to attribute huge importance to the tool used to make our art. But the SWC and I were figuratively connected at the hip. I still am in awe at what it allowed me to do, make pictures that span over 25 years of my career that are as close to me as anything I have ever done, seminal works that formed the basis for my practice. Finally, I learned much of the methodology from it that I still use today when I photograph, though I am now working exclusively with digital cameras.

This is a 903 SWC, like the model I owned. I sold mine a few years ago.

The last version of the camera was called the 905 SWC. Hasselblad stopped making the camera in 2005. Odd but this last one has a reputation of being the worst in all the years the camera was made. Hasselblad was required to change some of the chemicals they used for environmental reasons to make their lenses and the new formulation made the lens less sharp.

Other people that used or use it? Lee Friedlander comes to mind and Harry Callahan made many of his beach pictures with one, using a 645 back instead of the square.

As you know, my work is represented by 555 Gallery in Boston. Want to see any of the above portfolios? Just ask.