Sitting Around

Sitting around after dinner with friends the other day we got into a discussion that hit home for me. This concerned career development, connections made and lost and how many times I've been screwed by the dreaded "curator changeover".

I don't have any knowledge of business practice but it has to be true in that world too.

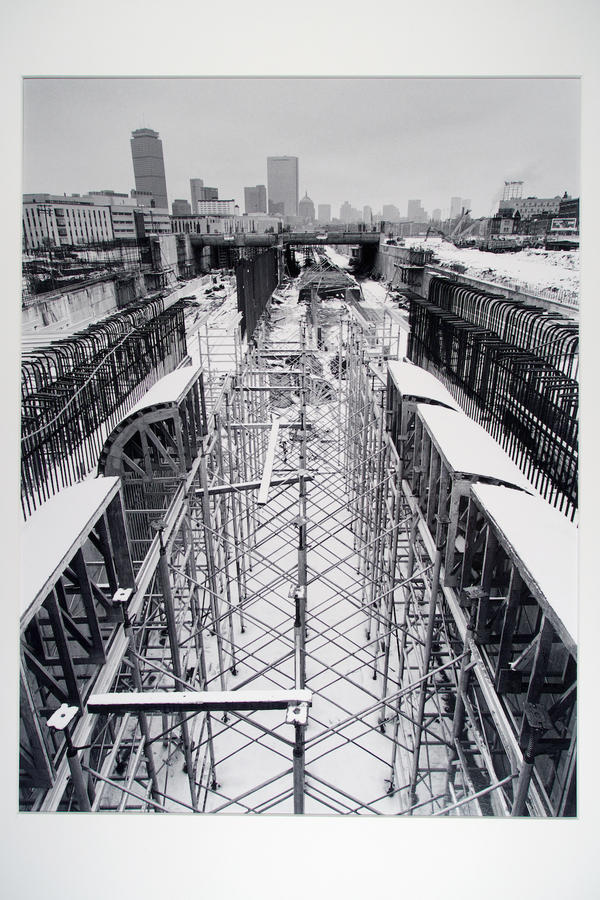

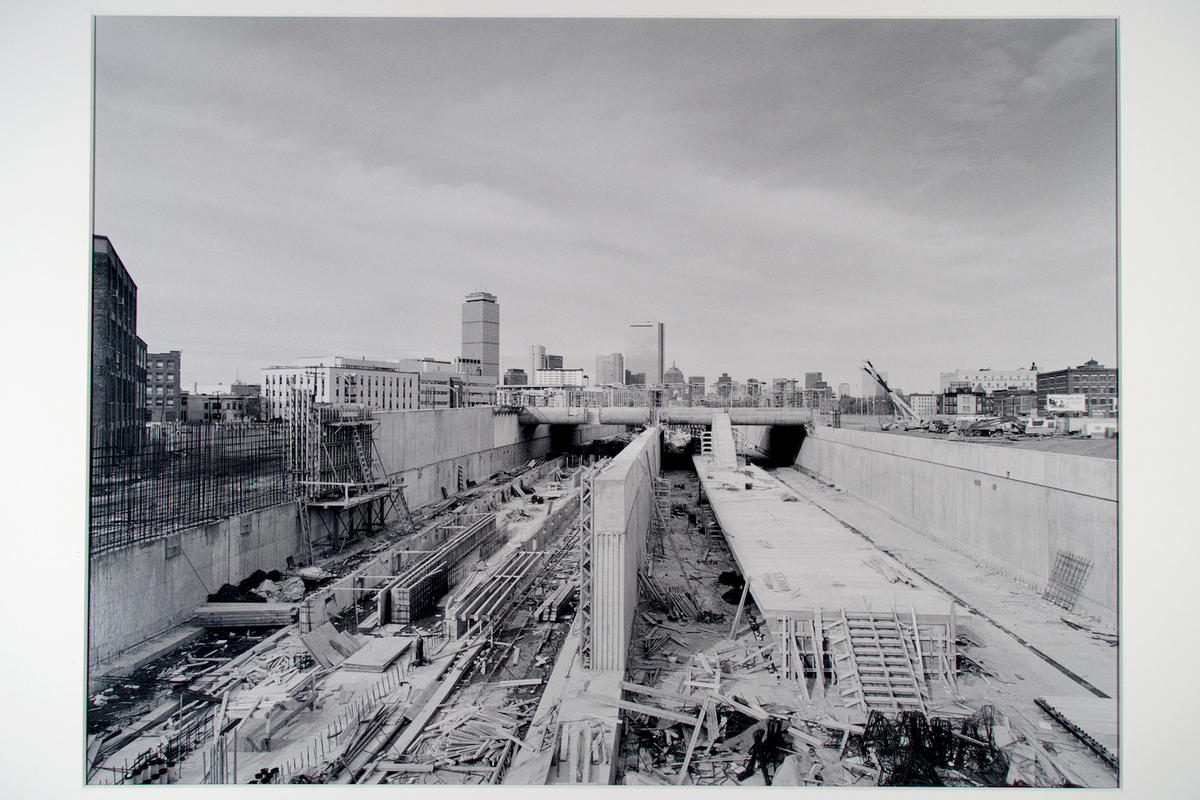

In a career that is based on showing museum curators my work towards purchase for their permanent collection and/or exhibition there have been many times where my work has been mishandled, poorly represented and misunderstood.

Let me give you a few examples. I studied at the RI School of Design in Providence, RI and it seemed logical to keep up contact with the RISD Museum of Art in the years after finishing. The Museum is the art museum for Rhode Island, not just for the school. So I did. Eventually, I was showing portfolios of new work every year or two to Diana Johnson, the museum's director. For whatever reason, Diana "got me" and had a strong sympathy for the work I was making and the direction my career was taking. Without my specifically asking she committed to showing my work in a one person show two years down the line. I was ecstatic. Much thinking and planning went into what I would show, how I would juxtapose one body of work against another, even the artist statement I would write, the size of the prints and so on. About a year before we were going to schedule the show, Diana abruptly left the museum, to return to her original career, which was wealth management! All this history with her was now gone, all the trips to Providence to show her work, all the long conversations we had about intent and result, all now irrelevent. My show was quickly assigned to a new curator, just out of graduate school, another Johnson, this one named Deborah. Deborah and I had no history so I started over. The first time we met, I showed her some work and she excitedly told me she'd found a date and location in the museum for my show. I knew at this point in my career I wasn't thought of as an A list artist, or someone to be headlined. But to be given space to show my work on a lower floor in a room that was just outside the Prints, Drawings and Photographs Department felt like being given a table next to the kitchen in a restaurant. Furthermore, the show was now going to open in early August the next summer. For most museums, August is the graveyard shift, when attendance is low and foot traffic almost non existent. We did the show, I was very pleased and proud of the installation, the work looked great but practically no one saw it. End of story number one.

Story number Two. A few years after getting my MFA in the early 70's and moving to Boston I had begun to show work to the logical museums and venues for exhibition in the area: the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Decordova Museum, Vision Gallery and the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, MA, among others. Perhaps my strongest connection was with Don Snyder who was the head curator at the Addison. Again, Don understood my pictures, my intentions and the level at which I worked. This was fairly early in my career so my ability to be verbally coherent about my work was hampered by shyness and a lack of eloquence (still true today) but the pictures spoke to Don and so he committed to exhibiting my photographs after two or three years of showing him work. In his heart, Don wanted to be teaching not curating so when Ryerson Institute in Toronto offered him a full time job he jumped at it. Me? I inherited a young new curator at the Addison, tasked to curate my show, who had some progressive ideas about exhibiting my work, including "informalizing" it. The show was schedueled at a better time than in Story Number 1 and was a moderate success but I didn't like the presentation very much. Unmounted prints covered with glass and pinned directly the wall, butted quite close to each other? Fine for a hallway gallery, or maybe a cafe' but not a prestigious museum. The lesson here? Watch out for the curator who wants to bend your work to his or her goals and aspirations. End of second story.

Having your work curated can be very good, of course, a melding of two minds on what work will be shown, how it will look and what it means. To be fair, I have had that, both with museums (a show at the Danforth Museum curated by Jessica Roscio comes to mind) and with galleries (Susan Nalband at 555 Gallery, which represents my work). But relinquishing control of your work to someone else is never easy. This is very much like working with an editor, of course, or a music director or a conductor. For me the characteristic of working with someone over years only to find they've moved on and left you to work with a stranger seems to pervade my career. I am sure it does many others as well. I call it curator changeover and it sucks, big time.

Last story, this one with a decidedly unhappy ending. For probably fifteen years I showed work to a curator at a nearby museum. While my career was ascending, so was hers. We did a few small things together over the years, a print or two of mine in a group show, a couple of things purchased for the collection. In what turned out to be her last year there I made the museum an offer they couldn't refuse and they bought a whole portfolio of work, a series of mine. Now we were getting somewhere. Then, suddenly, she was gone. I never knew details but the museum had a big shakeup when a new director came on board. Not only did I lose all those years of showing the curator work, when I met with her replacement, there was no chance of anything happening. It was clear to me my work was not the new person's idea of what the museum should be showing or collecting.

I am hoping you will keep these three stories in mind as you work to gain increased exposure for your work.

Just saying.