Bluff Utah

This is the fourth Southwestern series I've written about and the last from the time period of the mid to late 90's.

The full series is: here.

If you liked the others, Chaco Canyon, Bartlett's Wash and Moab then you 'll like this one too. If you didn't then you have one more to suffer through.

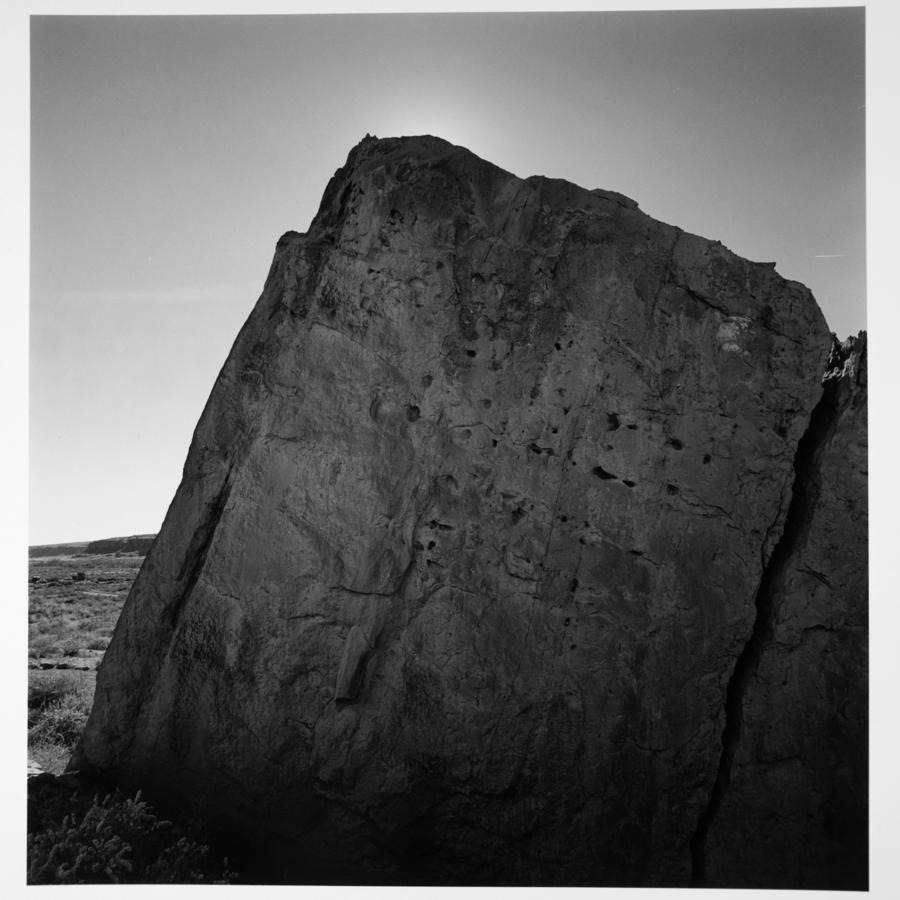

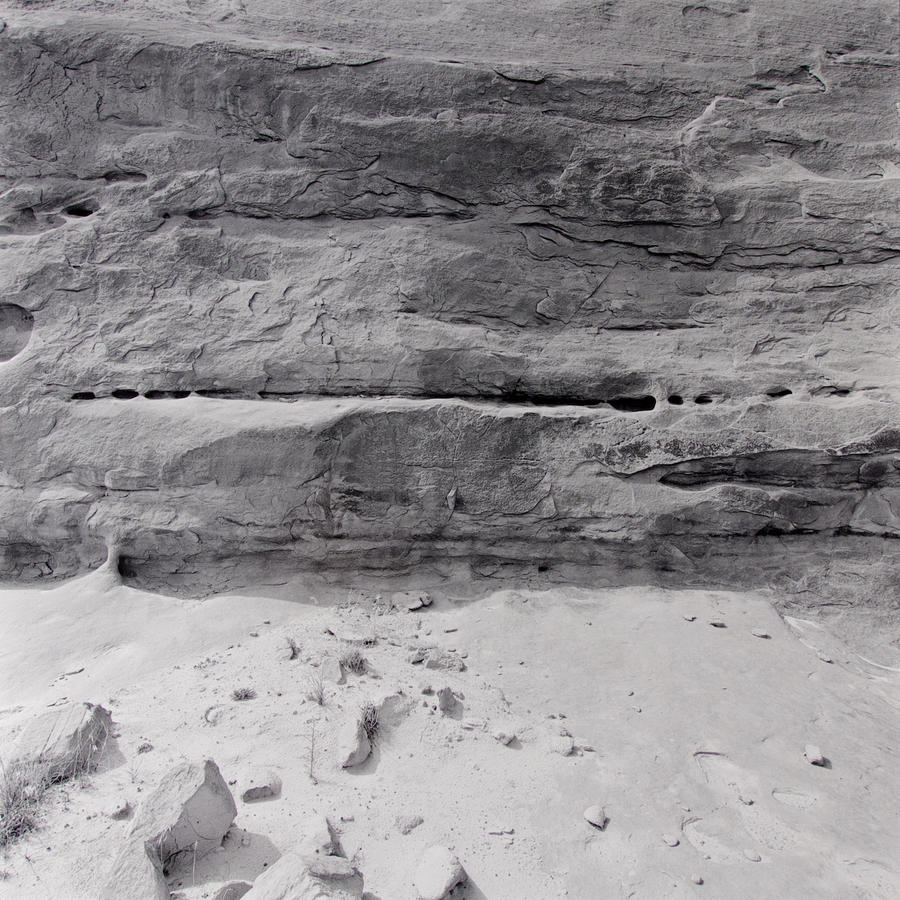

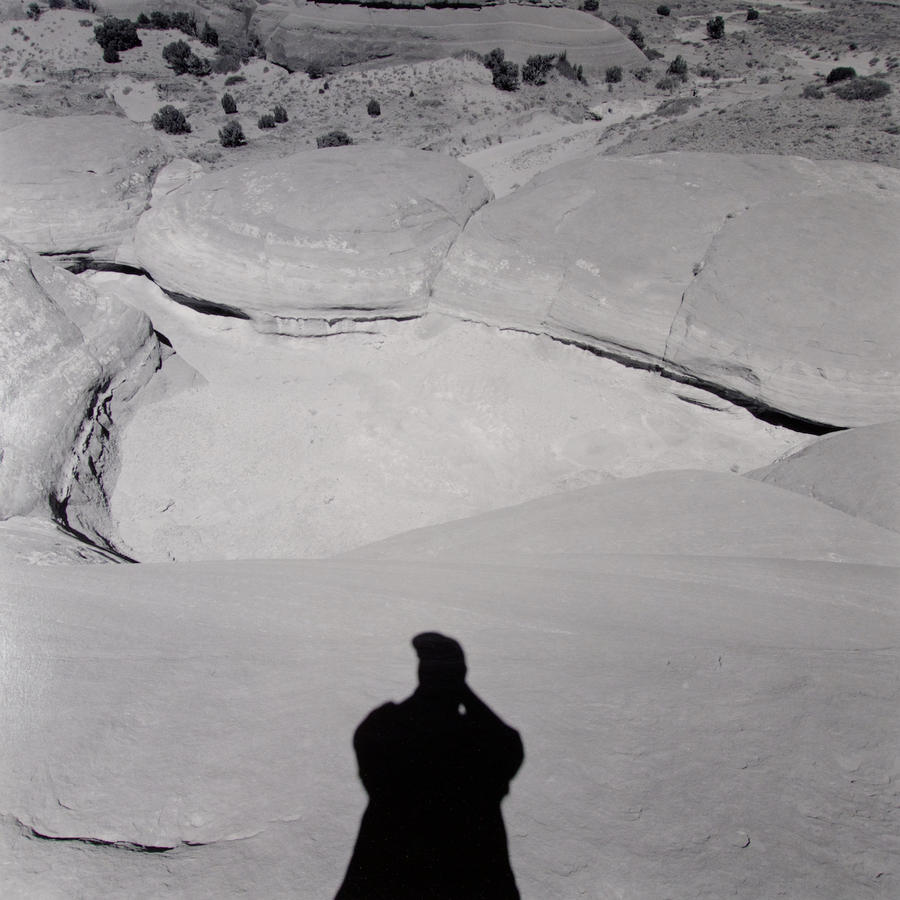

Bluff is a very small town on the southern edge of Utah in the southeastern corner of the state below Moab. It is mostly rock. I found these pictures while on a driving loop that was long and hot, stopping in Bluff to relieve myself but also on the hunt for pictures. I pulled over and took a short walk up a tight canyon far enough to see that I would need to climb to get to where the petrogylphs were. I'd been told back in town where to go. I went back to the car to gear up. In those days several rolls of Plus X 2 1/4 film on a belt pouch, a Pentax Spotmeter on a strap around my neck, and, in this case, hiking boots for traction that were also better protection if there were rattlesnakes, bottled water and a sandwich bought in town shoved in a backpack. No tripod needed here as it was bright sun. Finally, a note on the dash of the locked rented car saying who and where I was. And, oh yes, the Hasselblad Superwide in my right hand.

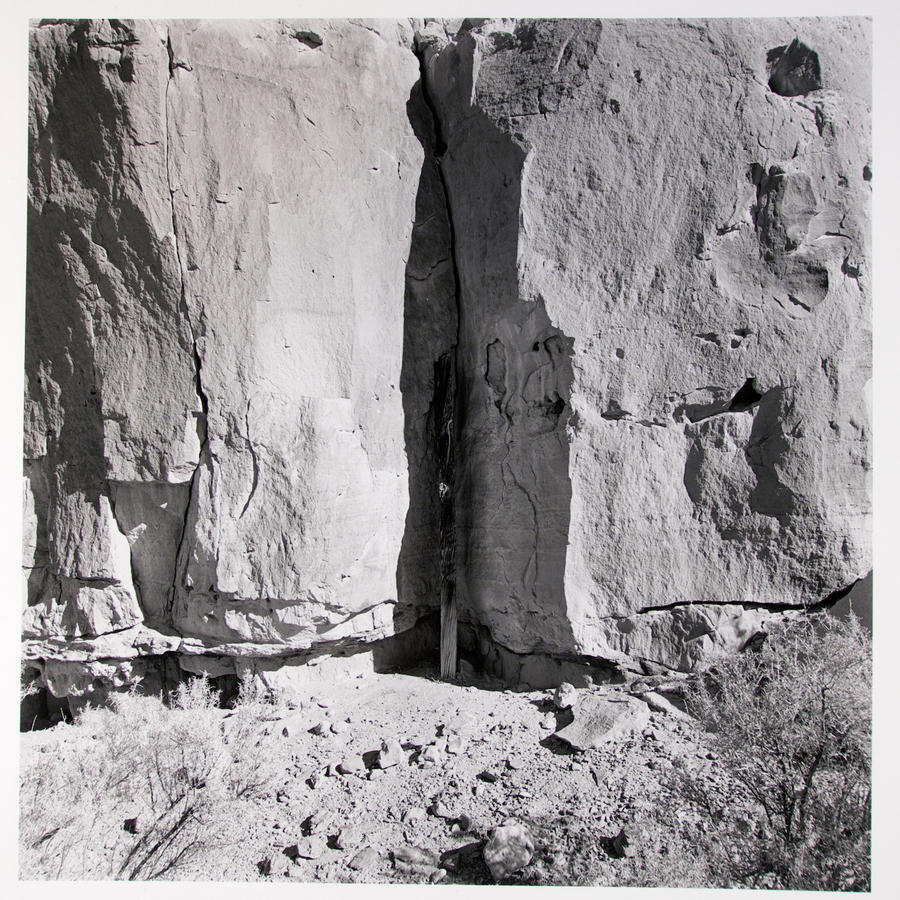

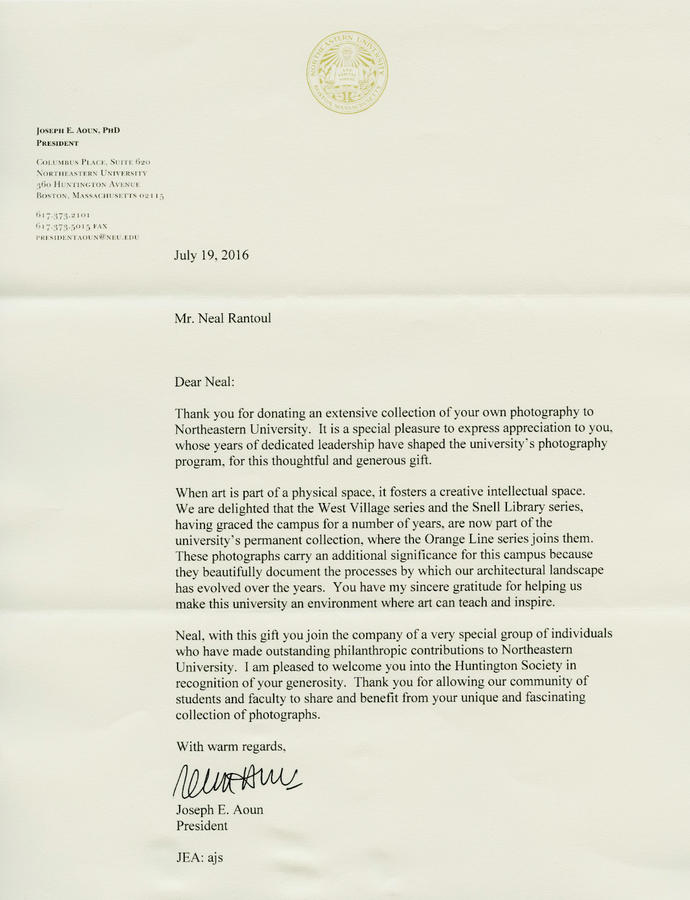

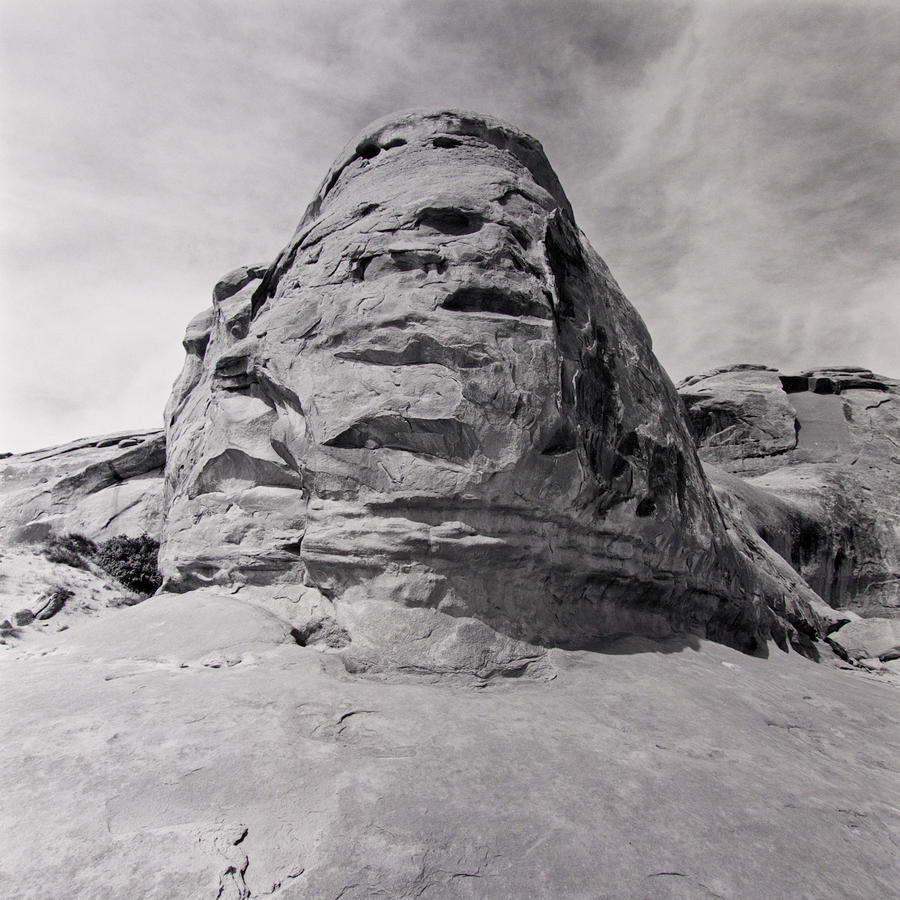

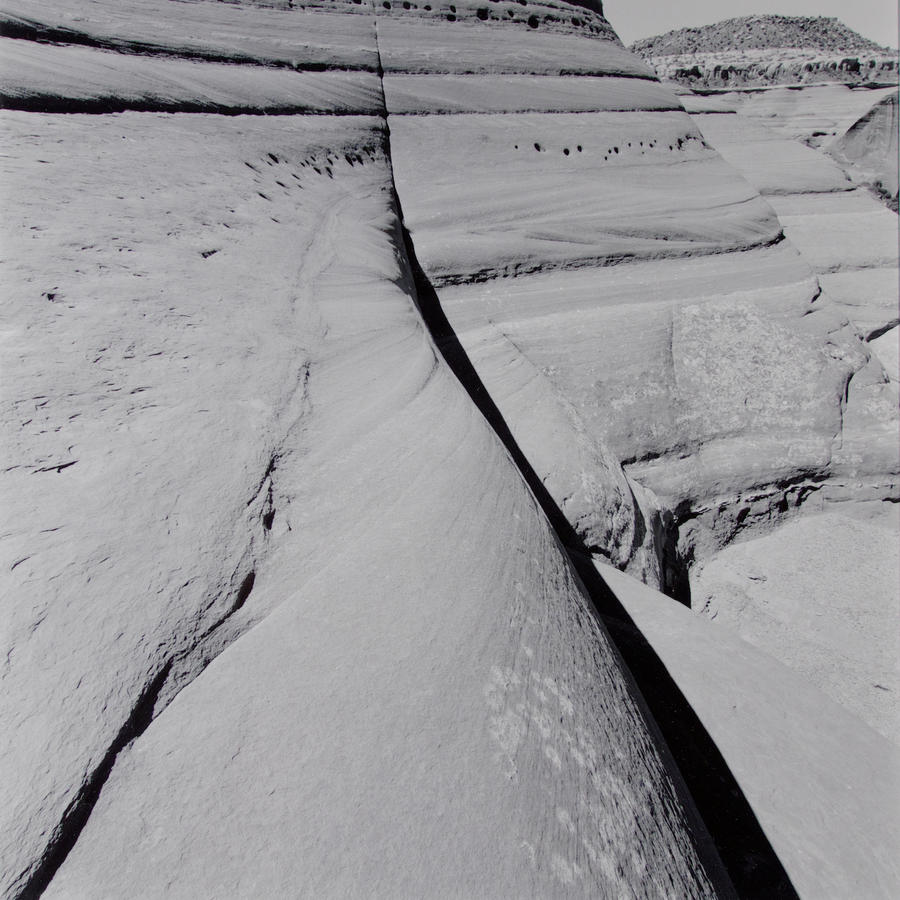

Climb up to a ridge, traverse it, then climb again over a small lip to higher ground that was like being on a plateau.

Let's pause here as presumably we're going on to more incessant pictures of rock and sky made in the American Southwest. All true. We are. How can someone do this? Stand in front of some rock in a barren landscape of rock and point a camera at it and trip the shutter? What possible reason would there be for doing this?

Presumably, we're going somewhere. Whereas a single photograph might be nice, it would really say very little. But put many together, take us somewhere, give us a narrative and the sheer reductiveness of the landscape might actually be used to make a point or to at least convey a broader and deeper sense of place and, in this case, the special nature of this place.

Is this just some middle aged New Englander white guy with a camera reacting to this most unusual of landscapes, responding to the differences between home and here? God, I hope not. Remember, by this time this kind of place is not new for me, this photographing in the Southwest.

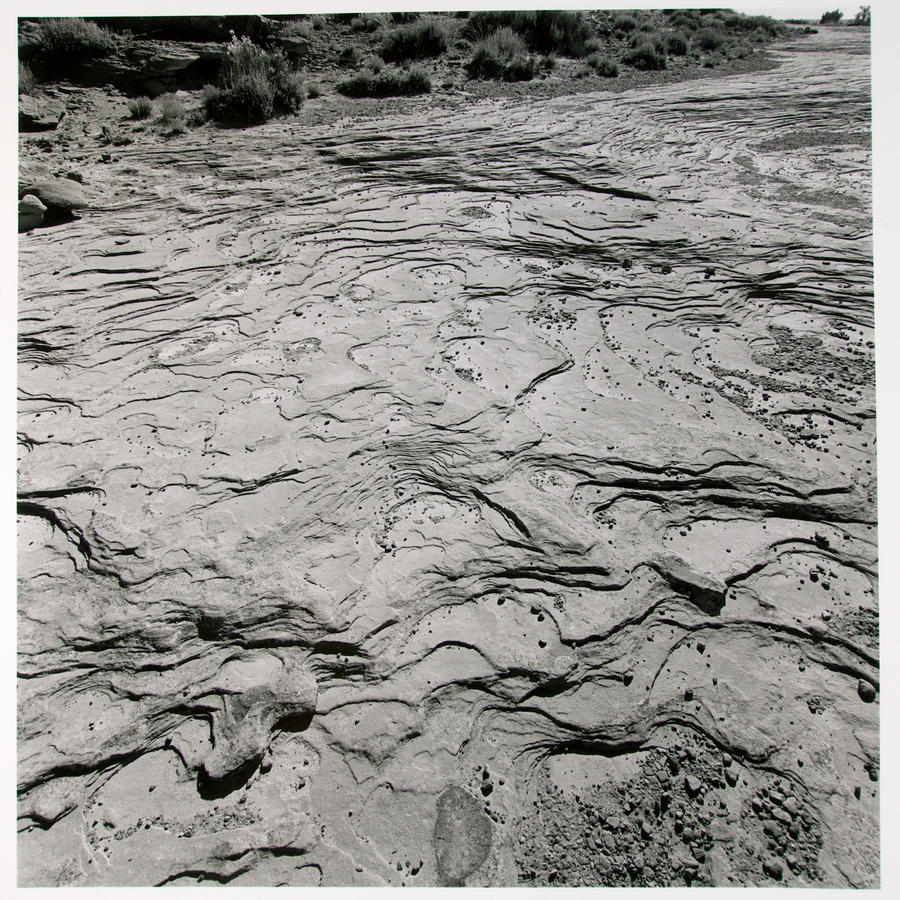

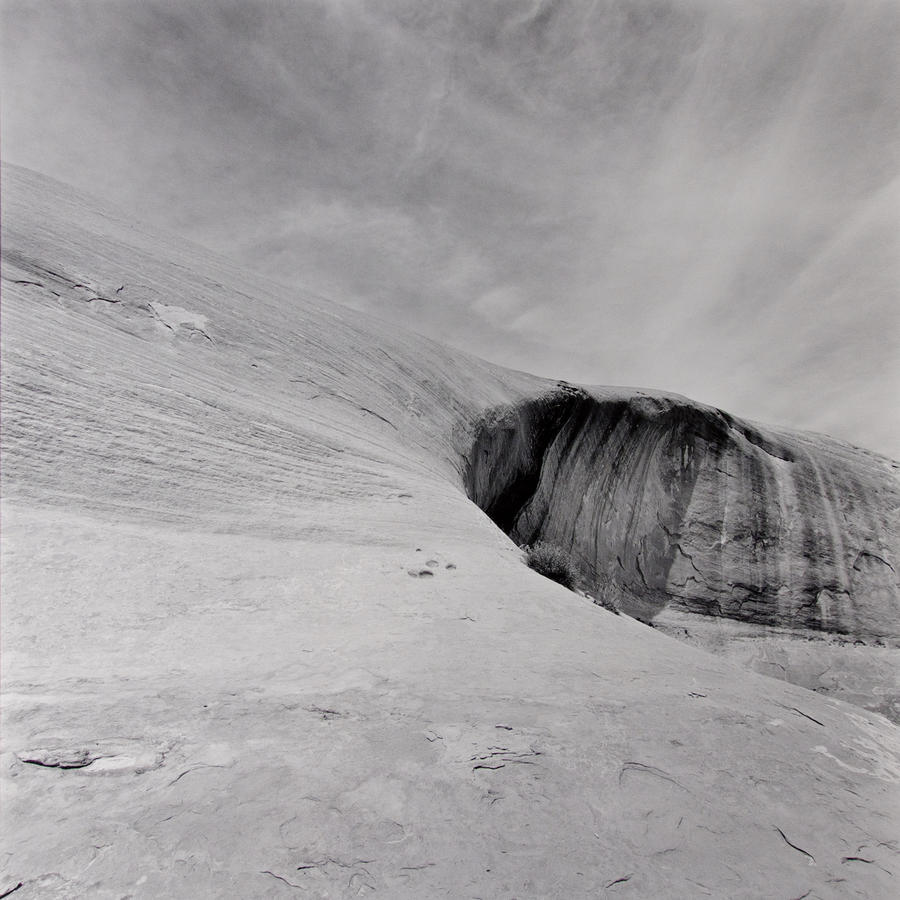

After a few more we arrive here:

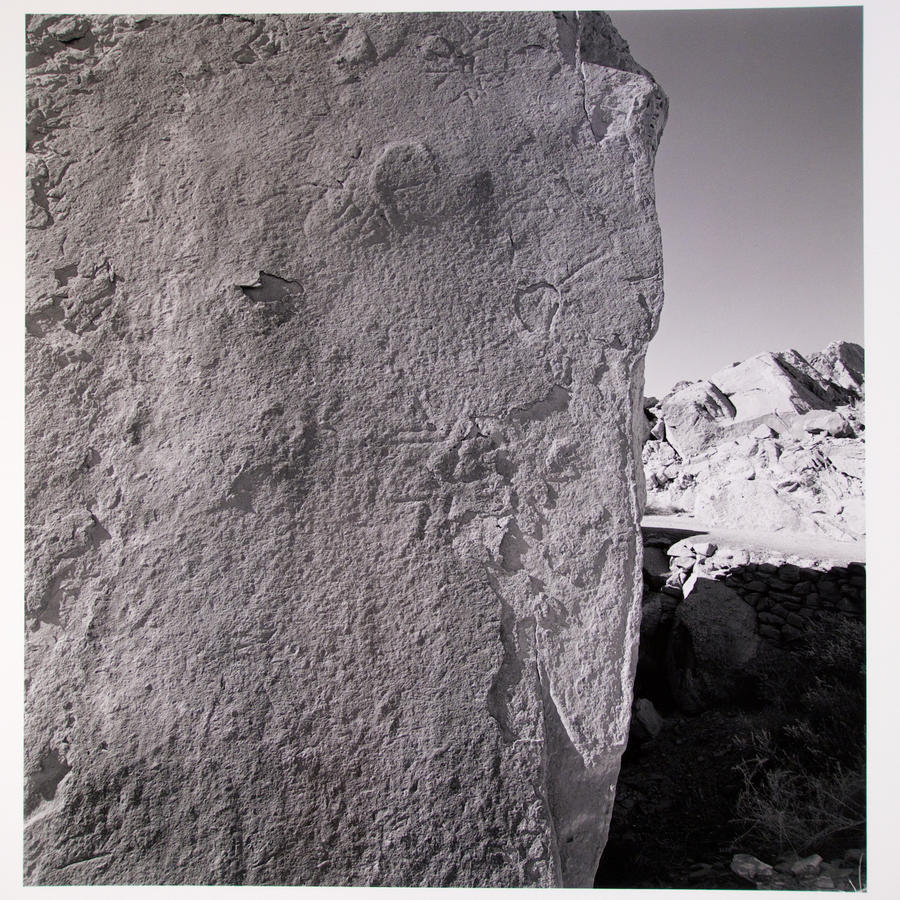

which begins to get us somewhere very specific. There have been people here and a very long time ago.

There is also a landscape bizarre and unique. No tourists, not on the map or at the end of a trail, no attraction. This made me feel unique, privileged to be in what turned out to be something of a sacred space.

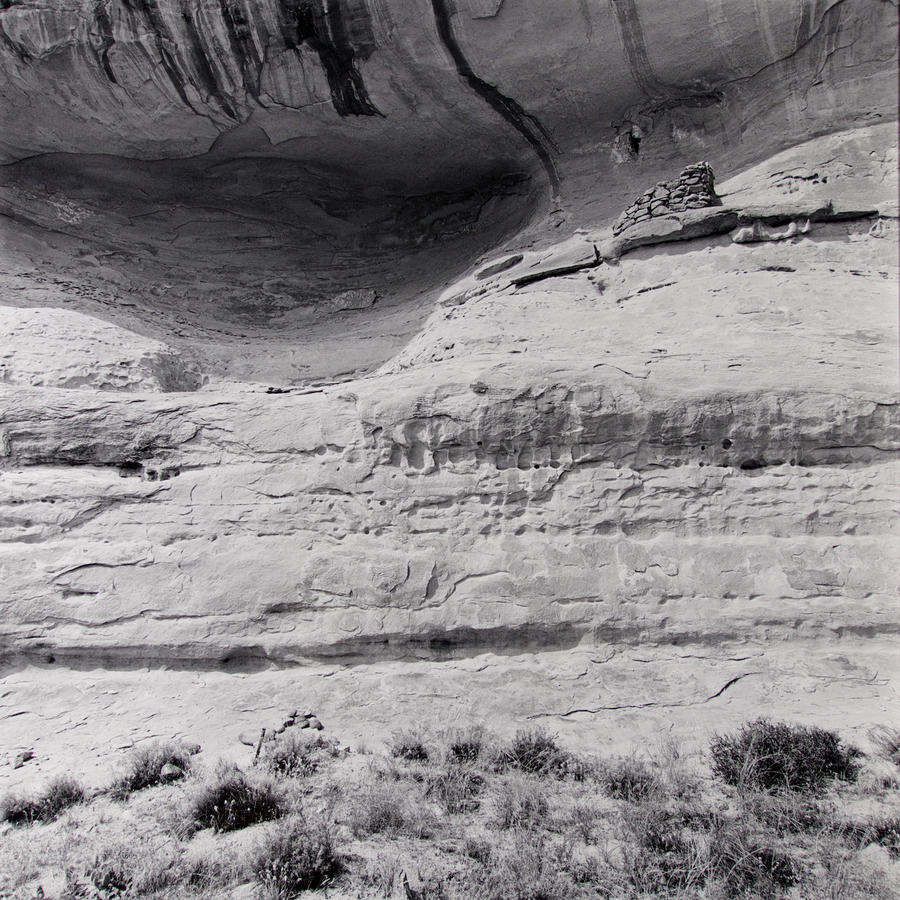

Here we are, finally, to a line of antelope or deer scratched out of the rock face how many years ago?

Sitting there, year after year, right there on a moonless night in February, with snow drifted up against the base of the wall or baking in the August sun, season after season. To, finally our own more present form of lasting, of preserving something of ourselves long after we are gone:

I remember being so offended at the discovery, from petroglyphs cherished for being authentic and a window into an honorable past to graffiti, the most recent carved into the rock just a few years ago, "DDRA or DORA 2-21-93", as though one was to be preserved and honored and the newer reviled as crude markings by teenagers clueless to our national heritage.

How did I end the Bluff Utah series? With this:

which was a symbol for me of both the real place, this ineffable shrine with something man made in the shape of a circle on the rock floor.

In the last scene in the wonderful 1982 movie "Blade Runner"directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, a "replicant" whose time has run out says, "I've seen things..."

I too have seen things.

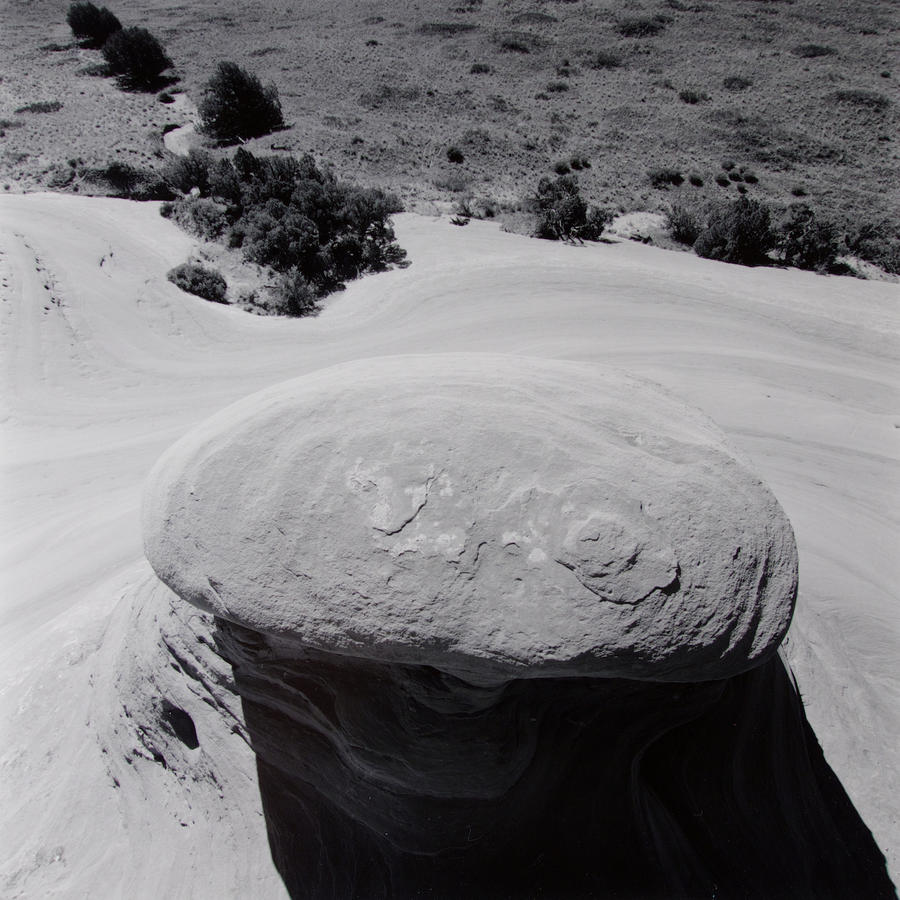

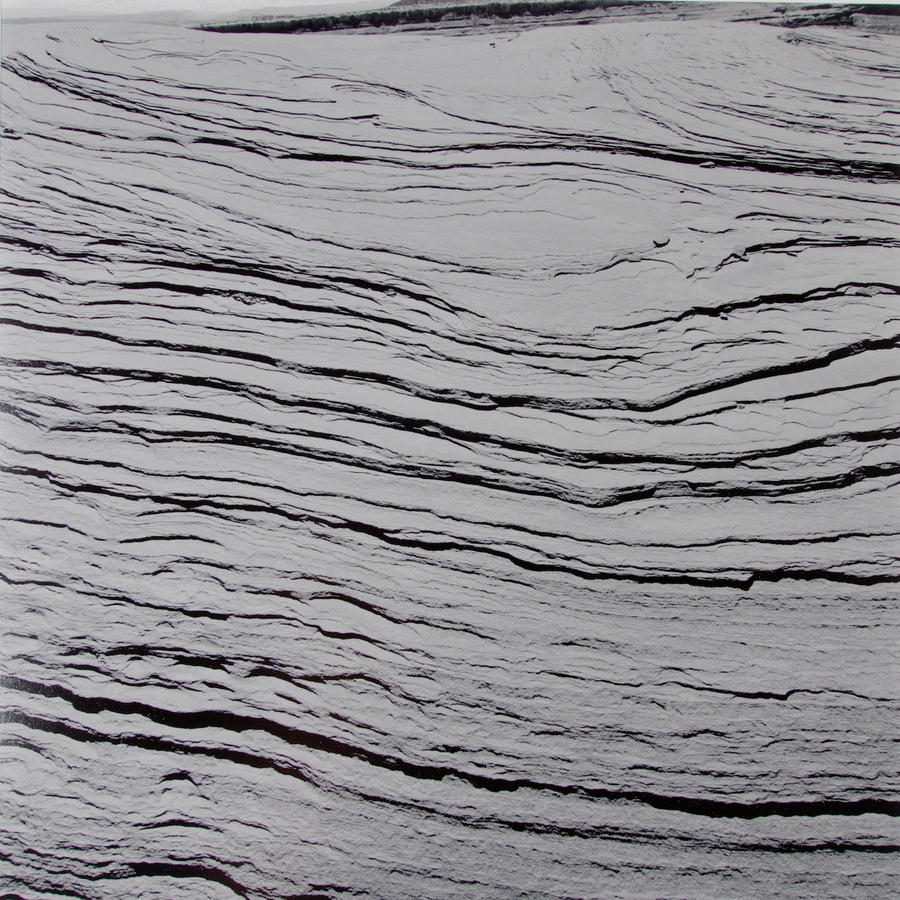

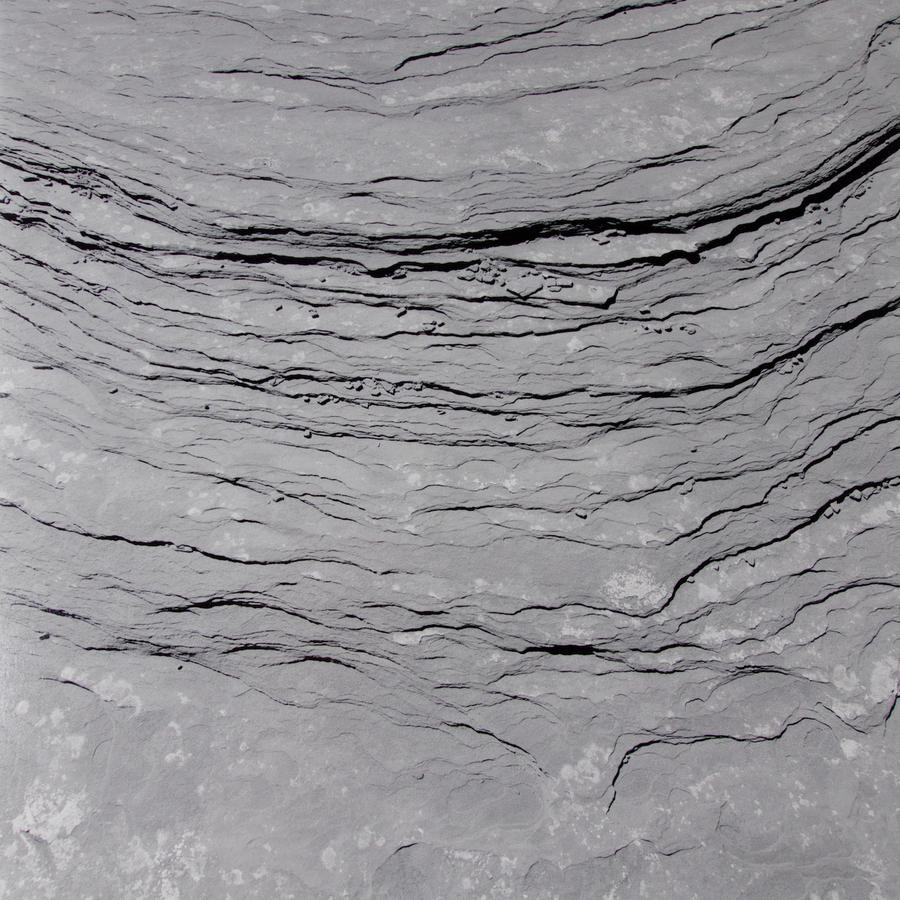

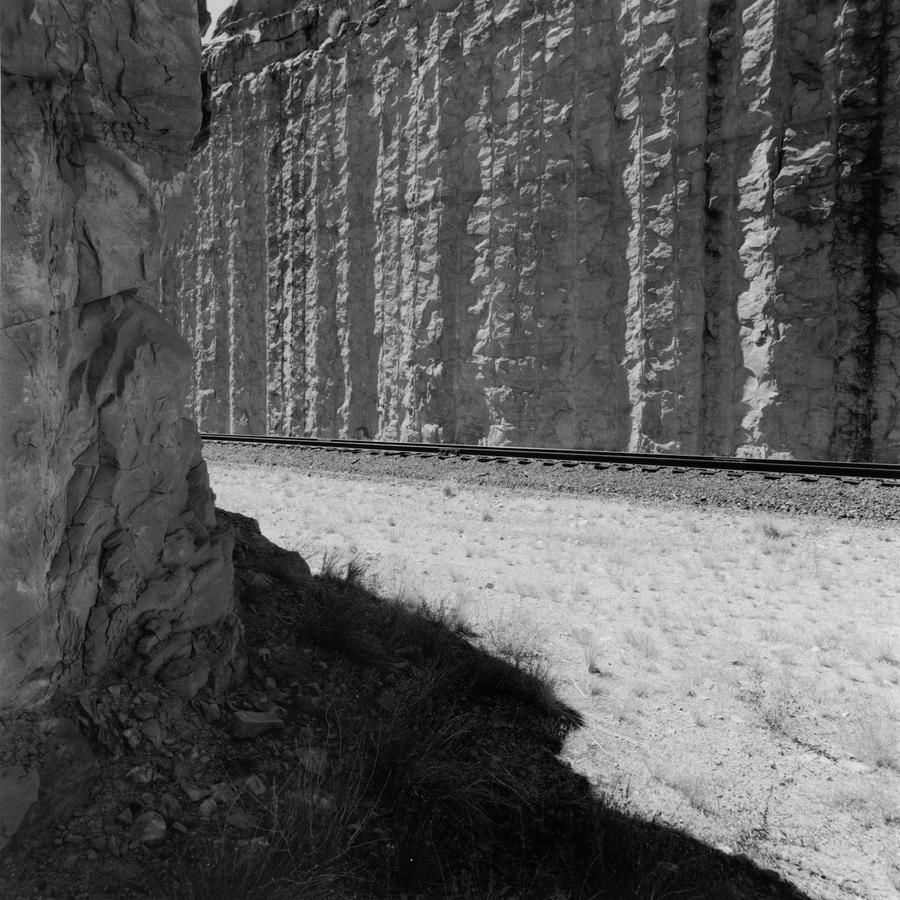

I liked the rawness of the place and its stillness, a path for the tracks blasted out of the solid rock. No trains came through while I was there. This is a sequenced body of work, meaning that the prints are arranged in an order. This is always done as I make the pictures and then in editing but in this case, as this is prints I made in the darkroom from film, by printing almost everything then arranging the prints over a period of days or even weeks to edit images out and to set a final sequence.

I liked the rawness of the place and its stillness, a path for the tracks blasted out of the solid rock. No trains came through while I was there. This is a sequenced body of work, meaning that the prints are arranged in an order. This is always done as I make the pictures and then in editing but in this case, as this is prints I made in the darkroom from film, by printing almost everything then arranging the prints over a period of days or even weeks to edit images out and to set a final sequence.

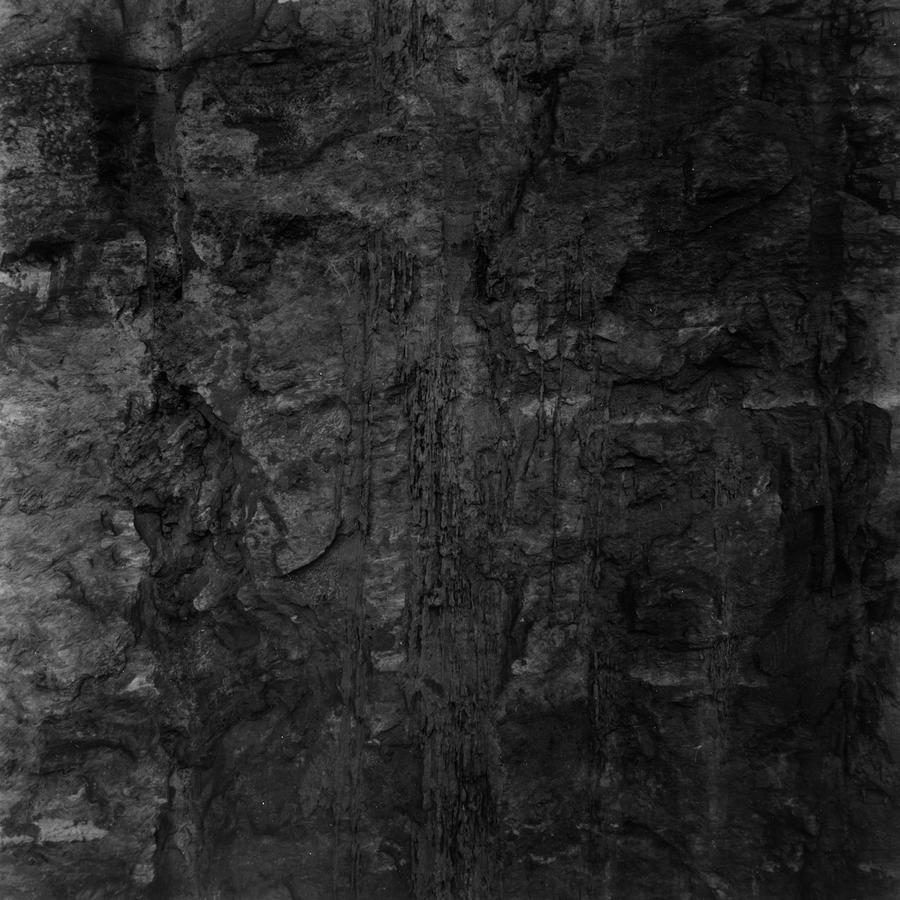

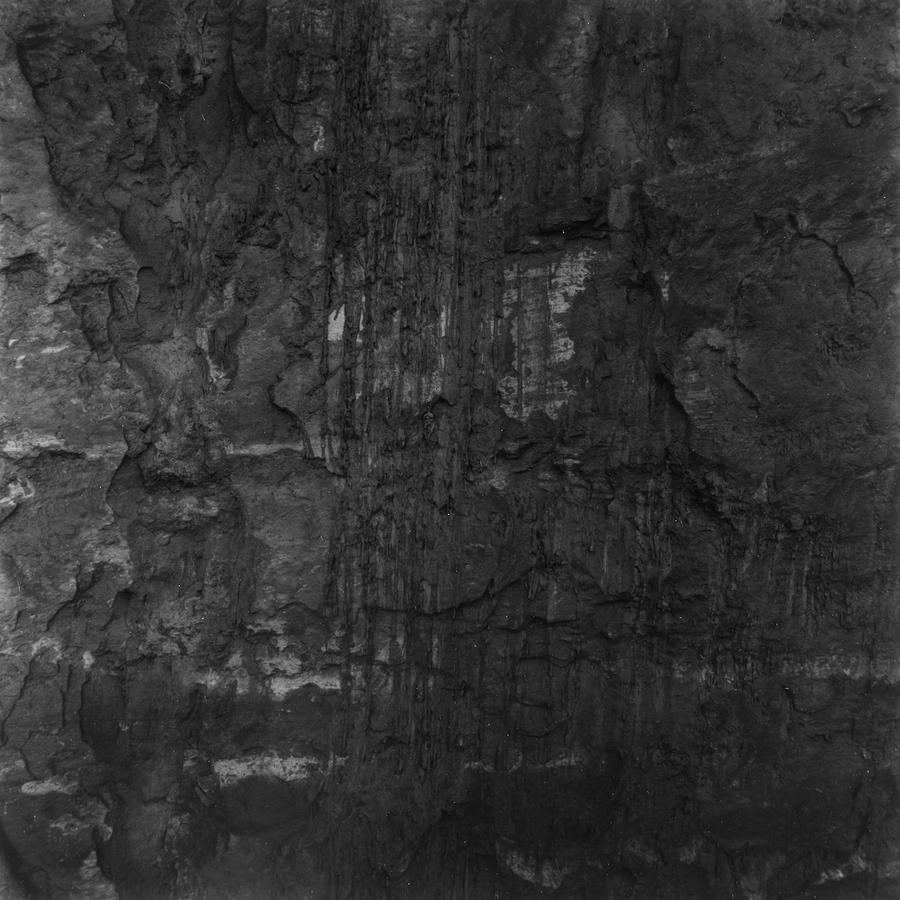

Also there are often pairings or subsequences within the overall series, as in here where I paired two together, both in the two above and also in the two below. I made the prints in my darkroom at Northeastern University where I taught. Most times I would go in early in the morning before my classes and print for a couple of hours.

Also there are often pairings or subsequences within the overall series, as in here where I paired two together, both in the two above and also in the two below. I made the prints in my darkroom at Northeastern University where I taught. Most times I would go in early in the morning before my classes and print for a couple of hours.

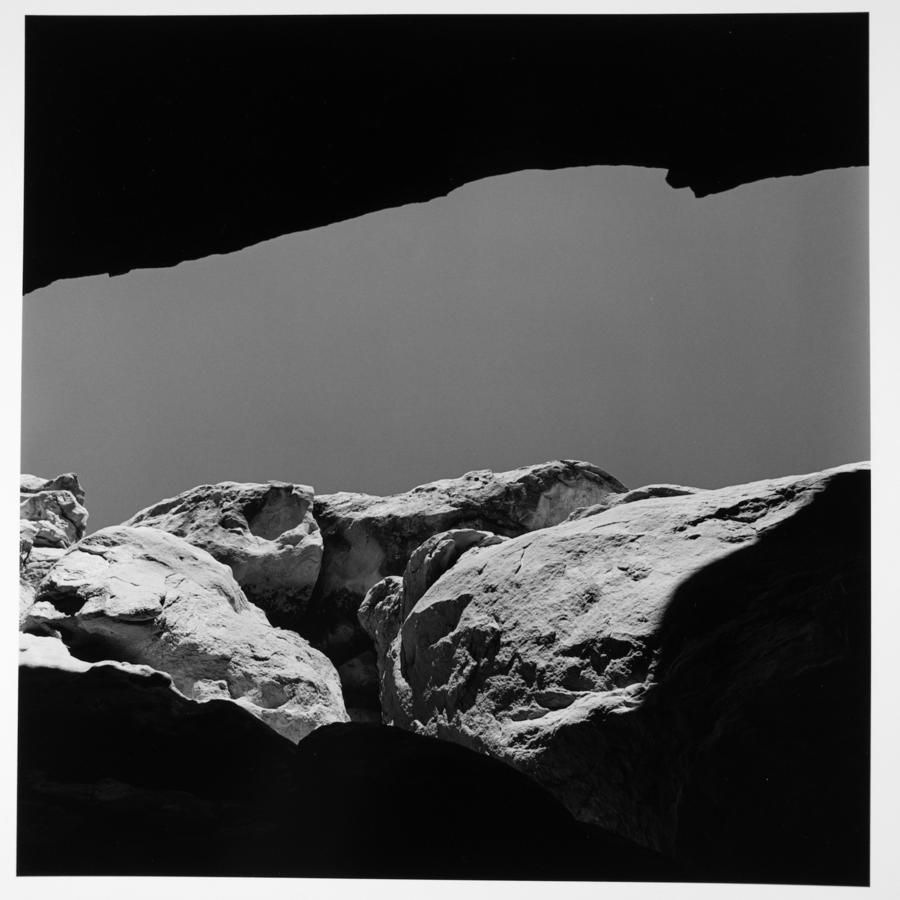

I remember using these two dark photographs as examples in my classes, trying to drive the point home about how exposure in the camera affects the final outcome. Photography is a little slippery in that what may look like some representation of reality, in fact, isn't. It is the medium's interpretation of the real. Knowing that we can bend the medium to our our desired outcome. In this case, you could either underexpose the film to make a thinner, more transparent negative with the final result being a darker print. Or, you could expose the negative normally (shot at Zone V, middle gray) and then push the print darker by exposing it in the enlarger longer. I wonder if you can tell which system I used here?

I remember using these two dark photographs as examples in my classes, trying to drive the point home about how exposure in the camera affects the final outcome. Photography is a little slippery in that what may look like some representation of reality, in fact, isn't. It is the medium's interpretation of the real. Knowing that we can bend the medium to our our desired outcome. In this case, you could either underexpose the film to make a thinner, more transparent negative with the final result being a darker print. Or, you could expose the negative normally (shot at Zone V, middle gray) and then push the print darker by exposing it in the enlarger longer. I wonder if you can tell which system I used here?

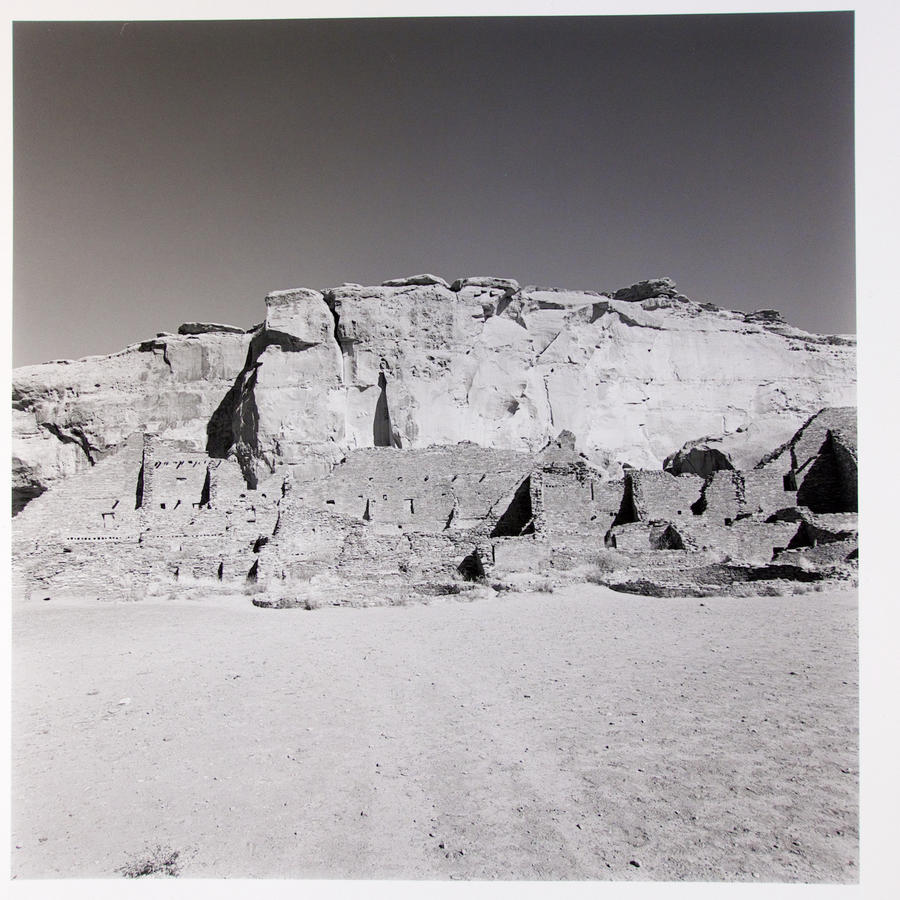

My series starts off with this one of the large great house called Chetro Ketl, but quickly leaves it as I headed up a trail that carves through the cliff face to arrive at the top looking out on the canyon below and the plateau above it.

My series starts off with this one of the large great house called Chetro Ketl, but quickly leaves it as I headed up a trail that carves through the cliff face to arrive at the top looking out on the canyon below and the plateau above it. Petroglyphs are common here.

Petroglyphs are common here.